|

Pictured below is a 'traffic filter'. It's a place where cycles, buggies, wheelchairs, scooters and people on foot flow through freely and comfortably -- albeit at the cost of cars doing so. That's why it's called a filter. This one's got a lot of charm. But a few bollards will do. In Oxford you can see them on East Avenue, Clive Road, Meadow Lane and elsewhere. It was at this particular filter that I met Fran (not her real name). I was asking passers-by what they thought of the filter and the overall changes to the neighbourhood. "Me?" asked Fran.. "I love it. I supported it from the start. But my husband didn't. It meant he had to drive 500 metres out of his way to get to work. And the through-streets were more clogged. But then he decided it made more sense to walk to work. And he did, and he's lost weight -- and I fancy him more!" That is traffic filtering. For driving, an added inconvenience. For health and social well-being, a major boost. It's a carrot and a stick. Fran's husband is getting a stick from the added nuisance of having to drive further to get out of his neighbourhood. But he has a carrot too. So what's the big deal if we already have these in Oxford (like this one on East Avenue, pictured below)? The big deal is that where I interrogated the passersby -- in the Blackhorse Village neighbourhood of the borough of Waltham Forest -- filters have been used to keep through-traffic out of neighbourhoods. These neighbourhoods range from ½ to one square kilometre. These are 'low traffic neighbourhoods' or LTNs (also known as 'liveable neighbourhoods'). The other characteristic of LTNs is that the whole area is taken into consideration. If, by closing one rat-run you would inevitably create another, you close that one too. The whole LTN is non-rat-runnable. To be clear: these are not street closures. All homes and addresses in an LTN are accessible by car. But it is no longer possible to drive through the LTN, from one side to the other -- as you can currently do on Littlehay/Cornwallis in Florence Park, for example. There is also no pedestrianisation necessary in an LTN. Waltham Forest did two high-street pedestrianisations as part of its overall programme, and those seem to have been the most controversial elements. The process of getting these LTNs implemented in Waltham Forest has been challenging. Such a major change to accustomed practice is understandably upsetting for many. In Walthamstow, there seems to be a kind of received wisdom about them. It goes like this: "Well, I like x, y, z aspect of [LTN], but... "if you lived on a perimeter road you'd hate them" or "if you were a trades person you'd hate them" or "they make me feel less safe". I asked Fran if the traffic behind us -- in the picture above -- was so bad. It seemed incredibly quiet. "That's the thing!" she said. "Everybody bangs on about the added traffic but actually some people must have changed their habits [like her husband!] because it's not that bad anymore." She's describing a phenomenon known as 'traffic evaporation'. Traffic is not a liquid that needs to go somewhere -- squeeze it out of one place, and it appears somewhere else. A portion of it just goes away as some people substitute into other modes. And indeed, at least at that point in time -- bang-on midday on a Thursday -- the roads flowed fine. Florence Park So why Florence Park? On 2 April, 2019, a local resident posted the following message on a neighbourhood-oriented discussion platform: 'Hi neighbors, a car almost hit me and my girls this week at the junction between Rymers, Littlehay and Cornwallis, and I was inspired to write to our County Councillor to ask him to make Flo Park safer for its pedestrians, cyclists and car drivers. Below is my letter - feel free to copy and then obviously change it to make it true to your own experiences..' The very next day, a local resident was knocked off her bike amidst a car collision in that very junction. She was hospitalised with multiple fractures to her pelvis. That's when the Florence Park Traffic Group formed, to hold a meeting in the community centre and discuss solutions. I've summarised that meeting here. The fundamental question is whether rat-running traffic has any business avoiding the main roads intended to be used for through-traffic. The view of Waltham Forest borough council was 'no' and, fortunately for them, they had a £29 million grant from Transport for London to start making changes. That figure is sometimes cited as a reason why LTNs cannot be done elsewhere. But it's not quite so. The £29 million funded a variety of improvements, of which the creation of LTNs via traffic filters was a small part. The figure for an area the size of Florence Park is likely to be between £50k-100k depending upon the types of filters used, approach to the Number 16 bus route, and other details. Cars or kids So it comes down to free-flowing cars or kids -- you can't have a neighbourhood with both. I've written about Britain's growth in car usage, and the trouble that's causing us as a society -- even if all the cars become electric. But we know for certain that any proposal to create an LTN will be upsetting. And many people will get organised. And they'll get the attention of councils. And that's why this has happened exactly nowhere apart from Waltham Forest. Twenty-one London boroughs bid for the £29 million grants. Only three of these were ambitious enough to be accepted. Of those, only one borough has gone through with it. But that's the thing -- the majority who appreciate these changes are pretty quiet about it, while the minority who loathe them are noisier. Why do I say the majority? Because when the Waltham Forest borough council went up for re-election in 2018, there was a real fear that voters would abandon the councillors who supported the scheme. Deputy leader Clyde Loakes as portfolio holder for environment was the most highly exposed to the protests, being the borough councillor most identified with the programme of liveability improvements. He penned his resignation letter before the elections. In the event, he was returned to office with the biggest majority in his 20-year career. Every single councillor who supported the changes was voted back in. What we hear about Waltham Forest, from the outside, is that the changes have been controversial. That's an understatement. But do the criticisms hold up? It might just be the case that there's a conventional wisdom about the changes, along the lines that despite the many benefits they've brought, they've created problems x, y and z. I will blog about those more specifically next time. But it reminds me of something Jacques Wallage (you can find him in this article) told an audience in Oxford about the liveability changes in Groningen, Netherlands forty years ago. "The only public voices we heard were against us. The police were against us. We would never have done it except that we knew it was the right thing to do." Many political groups have assumed control of the city's administration since then. Not a single one has dared undo those liveability improvements, nor would they have any reason to. The liveability of Dutch towns and cities is the envy of the world. Glossary

This blog contains the opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of any of the Co-CAFE team or Oxford Brookes University.

2 Comments

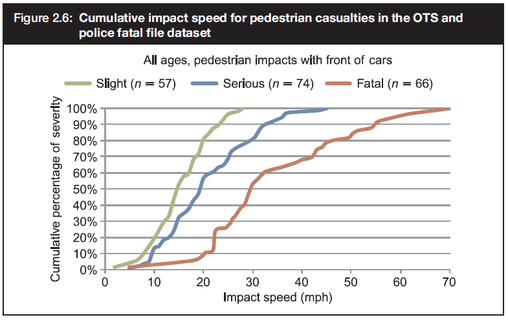

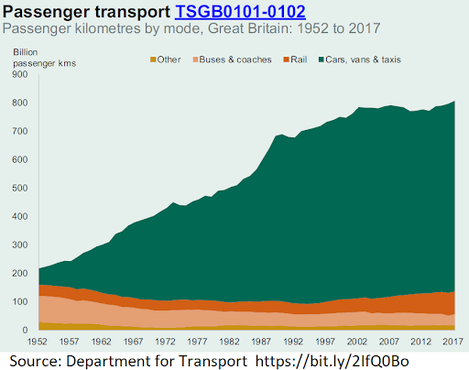

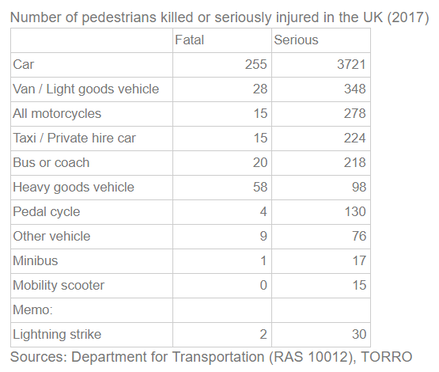

"Electric cars are the answer to today's challenges of air poisoning and climate change." Such a narrative is comforting for society and government. After all, it allows business-as-usual, with a few tweaks here and there. And that's why it's a disaster for liveability. Business-as-usual is killing us, maiming us and severing our communities. Even the 'green' credentials of electric vehicles don't entirely stand up to scrutiny. The government's Air Quality Expert Group last week stated that "particles from brake wear, tyre wear and road surface wear currently constitute 60% and 73% (by mass), respectively, of primary PM2.5 and PM10 emissions from road transport" (AQEG 2019). In other words, more of the particulate pollution in our brains, placentas and heart lining is due to non-exhaust features of cars than to the exhaust itself. We are also turning a blind eye to the carbon embedded in the manufacture of cars, as well as the negative externalities associated with commodity extraction for batteries, metal and plastic. Even if you haven't or don't question electric vehicles' green attributes, overlaying them in place of petrol and diesel ones perpetuates the liveability dilemma. Cars project an envelope of danger around them. A modest volume of car traffic transforms the street into a no-go area. For the very young and old, the public realm -- i.e. space outside, in built-up areas -- is too often a small strip on the margins of an abyss. Here's what I mean: Cars are 3-tonne hulks; humans are squishy 10-stone things. If you are hit by a car, the probability of survival is an exponentially decreasing function of that car's speed. The figure below reports that about half of the fatally injured pedestrians in a 2010 Department for Transport dataset were hit at an impact speed of 30 mph or less. On the residential estate of Florence Park, Oxford, I sometimes hear from our elder residents that "the streets used to be safer" or that "kids used to play in the streets". In my view, what's changed isn't X-Boxes or iPads. It's cars. I've heard many residents say it: There are simply more cars on the road today. The UK overall numbers bear that out: Combine cars' envelope of danger and their ubiquity and you get four thousand pedestrians killed or seriously injured in the United Kingdom in a single year (see table). For the sake of convenience and business-as-usual, cars get a special exemption from society's critical thinking. It's as if we are victims of a transport-oriented Stockholm syndrome. So the envelope of danger is real. But the casualties go further. Cities, towns and neighbourhoods are places where people are meant to mingle. That's less likely where the public realm is so dominated by danger. People don't normally like to gather or just casually hang out on the margins of a cliff. Donald Appleyard, the UK-born academic, twigged this forty years ago. In Livable Streets, Appleyard presented his research into San Francisco's neighbourhoods. The upshot was that residents of neighbourhoods with busy roads reported far fewer social connections on their street. It's well worth looking at this video inspired by Appleyard's research and checking out people who cite Appleyard as an inspiration for their own work. Appleyard was actually a latecomer to liveability. A decade earlier, Amsterdam kids were actively fighting the onslaught of cars, as documented in this must-see vignette from 1972. Electric vehicles change none of this. As my friend Danny Yee says, the volume of cars on the roads should be reduced by 80%, and the remaining 20% should be electric. To worry about the latter and not the former is no solution at all. It's business as usual. So what is to be done? I'll sketch that out in the next blog post. SOURCES Air Quality Expert Group (2019), "Non-exhaust emissions from road transport" (DEFRA) Appleyard, D. (1981), Livable Streets (University of California Press) Department for Transport (2018), "Transport Statistics Great Britain" Richards, D. (2010), "Risk of fatal injury: Pedestrians and car occupants", Department for Transport (London) The Tornado and Storm Research Organisation (TORRO) This blog contains the opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of any of the Co-CAFE team or Oxford Brookes University.

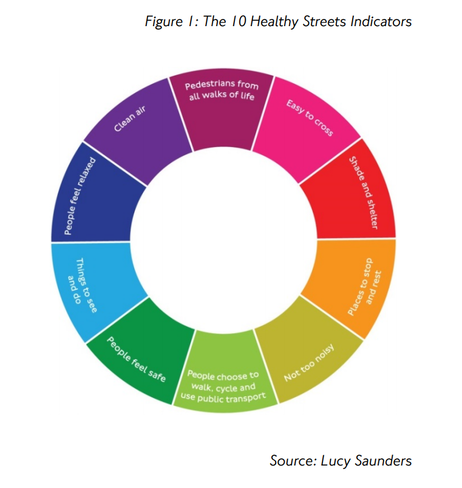

Three masters students of urban planning from Oxford Brookes University are to survey the Flo Park Community in order to better understand feelings and concerns towards their local built environment. The surveys will be based on the Healthy Streets Approach Survey. The Healthy Streets Approach puts people and their health at the centre of decisions about how we design, manage and use public spaces. The Healthy Streets Survey questionnaire asks people walking and dwelling on a street about how they perceive the street e.g. how attractive and enjoyable they find it to be there. In asking these questions the Healthy Streets Survey aims to capture the ‘real-life’ experience of people in their streets in relation to the 10 Healthy Streets Indicators In addition to the Healthy Streets Survey questions, the students will create questions related specifically to local challenges in Flo Park and that relate to each of the student’s dissertation topics - including walking, cycling and transport. There is a possible inclusion of some qualitative questions to be considered, if the time frame for evaluation allows.

The survey is to be in a written format and to be kept as simple as possible, using the 10 main indicators as a guide from the Healthy Streets Approach. The questions are to be emailed to FloPark Traffic group for comment before being distributed. The students are to distribute a total of 1,300 surveys to the homes of Flo Park residents, using a drop and collect methodology with addresses being selected at random. There is also the possible option of using self addressed envelopes (SAEs) to allow for a free postal returns or a return box to be set up in the Community Centre. The term ends for Oxford Brookes University students in mid July and the student’s dissertation submission date is 28th September. Contact [email protected] to get involved or for more information. |

AuthorsCo-CAFE is led by Tim Jones (Reader in Urban Mobility) with Ben Spencer (Research Fellow) and Tom Shopland (Co-CAFE project administrator) based in the School of the Built Environment at Oxford Brookes University. Archives

February 2020

Categories |

|

Oxford Brookes University

School of the Built Environment +44 1865 48 4061 |

|

Funded by the Lifelong Health and Wellbeing cross-Council programme. Grant No. EP/KO37242/1

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed